“My folks sell me and yo folks buy me”

Kanye West, “Barracoon” and some history of African slavery

Do you recollect the uproar caused by the musician Kanye West a couple of months ago when he said the ancestors of today’s African-Americans “chose” to remain in slavery? Arguments bounced around the word “choice.” What choices did slaves have? What choices do African-Americans have today? One point about slavery went unmentioned though. Most African slaves were sold into slavery by other Africans: by African kings, aristocrats, warlords, state officials and merchants. That was also a choice. As Gumpa, the leader of a group of newly emancipated American slaves put it, according to the recently published slave narrative Barracoon: “My folks sell me and yo folks buy me.”

Do you recollect the uproar caused by the musician Kanye West a couple of months ago when he said the ancestors of today’s African-Americans “chose” to remain in slavery? Arguments bounced around the word “choice.” What choices did slaves have? What choices do African-Americans have today? One point about slavery went unmentioned though. Most African slaves were sold into slavery by other Africans: by African kings, aristocrats, warlords, state officials and merchants. That was also a choice. As Gumpa, the leader of a group of newly emancipated American slaves put it, according to the recently published slave narrative Barracoon: “My folks sell me and yo folks buy me.”

This fact is not irrelevant today when we’re often asked to see the situation of African-Americans as mainly a matter of historical white guilt and black victimhood. If you want to racialize historical guilt – a mistake anyway – then there’s guilt enough to go around.

Kanye West

Here’s what Kanye West said on the ‘entertainment website’ TMZ, on May 4:

“When you hear about slavery for 400 years… for 400 years? That sounds like a choice. You was there for 400 years and it’s all of y’all? It’s like we’re mentally imprisoned. I like the word 'imprisoned' because slavery goes too directly to the idea of blacks. It’s like slavery, holocaust, holocaust, Jews, so slavery is blacks. So prison is something that unites us as one race. Blacks and whites being one race. That we're the human race. That we’re human beings and stuff.”

West later clarified: "to make myself clear. Of course I know that slaves did not get shackled and put on a boat by free will," and “My point is for us to have stayed in that position even though the numbers were on our side means that we were mentally enslaved."

The usual outpouring of outrage and offense-taking ensued:

Kanye West was endorsing the white supremacist depiction of the slave as faithful, contented servitor, ever grateful for massa’s benevolence. Didn’t he know the list of 250 slave revolts in the United States compiled by the communist historian Herbert Aptheker? [1]. Perhaps illogically, critics also denounced West for insinuating that, if in the past blacks could have “chosen” to rebel against slavery, so today they can reject the “mental slavery” of seeing themselves as forever the victims of history, ever dependent on government benevolence. The racialist writer Ta-Nehisi Coates berated West for “collaborating” with the white man.

Professors Glenn Loury and John McWhorter – the self-described “black guys at BloggingheadsTV” – explored what Kanye West might have been trying to say. Here’s Glenn:

I think what he probably, kind-of meant to say…is that there’s a slave mentality that you can choose to live within, or you can choose to throw off…here we are in the year 2018, talking about slavery. Every third word is about slavery. Now, as I’ve said before, the failures that are palpable, that stare us in the face, cry out for some such false narrative. And for a rapper of some celebrity to point out: “False narrative, Y'all. Slavery has been over for a long time. Can we please get on with the business at hand, which is making our way in a competitive world? It’s not going to be easy. It’s going to be hard. No one’s coming to save us. No one’s coming to give us a damn thing. Get busy, like I got busy. I made me; you make you. OK?” Now I’m not endorsing every word of that. But what I’m saying is that there’s no reason for the skies to fall, for people to roll in the streets heartbroken at the betrayal of somebody, for saying something that’s as necessary to be said, right or wrong, as that.

Glenn went on to even trickier ground:

There are questions if you’re prepared to have philosophical courage, about whether or not, if faced with the choice between slavery and death, and you choose slavery, that’s not a choice. That’s a serious philosophical question. You can put it to the Jews who confronted death camps. You can put the same kind of existential, philosophical question … Now, you want to put it very carefully. You want to put it in very close context. You want to be seen not to be blaming the victim for the awful holocaust which befell them. But, nevertheless, there is a question about whether or not a person … doesn’t have an obligation to fight to the death under such circumstances of degradation as those associated with slavery.

Choices under slavery

The violence of the reaction to Kanye West suggests many people think any talk about the choices available to slaves must imply some endorsement of slavery. But this is a logical non sequitur: it does not follow. Slavery – depriving human beings of their natural rights to “life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness” – is an objective moral wrong, regardless of anything the slaves might or might not have done.

Although slaves never let themselves “get shackled and put on a boat by free will,” as Kanye West stipulates, they still had real choices about how to resist enslavement. These choices ranged from mass insurrection – and probable death – to surreptitious individual assassinations, running away, perhaps to settlements of escaped slaves in the wilderness; theft, sabotage, resistance to work discipline, cultural resistance, and much else, all the way to grudging acquiescence and accommodation. These were practical choices. Slaves were rational human beings. They had agency. They chose how best to resist slavery and pursue happiness according to the circumstances they faced. The forms and extent of slave resistance were therefore highly variable in different places and times.

Slave revolts in the American South, for example, “did not compare in size, frequency, intensity or general historical significance with those of the Caribbean or South America,” according to Eugene Genovese. [2]. Most of the 250 American slave revolts listed by Herbert Aptheker were small, usually of many fewer than 100 people.

The reason seems straightforward. Slaves in the United States were both fewer in number and more dispersed than in the Caribbean or Brazil, or in the great slave revolts in history such as the revolt of Spartacus in 73 BCE, the revolt of the Zanj (African slaves) in Iraq in 869-883 CE, or the Haitian revolution of 1791-1804. Robert Fogel says there were six times as many blacks in the British Caribbean in 1700 as there were in all of the North American colonies. He ascribes the relatively small numbers to the minor part of the sugar industry in the growth of U.S. slavery.

Slave numbers grew over the 18th century with more tobacco, indigo and rice cultivation. But slaves were still only 40% of the population in the American south in 1770, compared to over 90% in the British Caribbean. There was new demand for slaves on cotton plantations in the 19th century, but, after the abolition of the external slave trade by the United States in 1808, this had perforce to be met from the existing slave population. Fogel says the pattern of U.S. crop specialization also affected the size of units on which slaves lived and the development of American slave culture. The median number of slaves on U.S. cotton and tobacco plantations was well below 50 – dwarfed by the numbers on the sugar plantations of the Caribbean and South America. American slaves came into closer continuous contact with the European culture of the slave owners than anywhere else. [3]

Barracoon

Barracoon is the narrative of Oluale Kossola – Cudjo Lewis – one of the last surviving African-born American slaves. Raiders from the slave trading warrior kingdom of Dahomey captured Kossola in 1859 and sold him to William Foster, captain of the Clotilda, out of Mobile, Alabama, on what was the last cargo of slaves smuggled into the United States. The African-American anthropologist and novelist Zora Neale Hurston interviewed Kossola in 1927-28. Amazingly, this powerful and revealing record went unpublished for almost a century, until brought out by Harper Collins in May 2018.

In her Foreword the novelist Alice Walker writes:

Reading Barracoon, one understands immediately the problem many black people, years ago, especially black intellectuals and political leaders, had with it. It resolutely records the atrocities African peoples inflicted on each other, long before shackled Africans, traumatized, ill, disoriented, starved, arrived on ships as “black cargo” in the hellish West. Who could face this vision of the violently cruel behavior of the “brethren” and the “sistren” who first captured our ancestors?

Reading Barracoon, one understands immediately the problem many black people, years ago, especially black intellectuals and political leaders, had with it. It resolutely records the atrocities African peoples inflicted on each other, long before shackled Africans, traumatized, ill, disoriented, starved, arrived on ships as “black cargo” in the hellish West. Who could face this vision of the violently cruel behavior of the “brethren” and the “sistren” who first captured our ancestors?

Who indeed?

Kossola was born around 1841, a member of Isha subgroup of the Yoruba people in West Africa, in the town of Bantè, in what is today west-central Benin. His narrative gives a glimpse of slavery as a widespread, indigenous African institution. He recalls his grandfather, a notable of the tribe, who possessed many wives, children – and slaves. After a big meal, Kossola’s grandpa would take a nap, attended by his younger wives:

Somebody stand guard before de door so nobody make noise and wakee him. Sometime de son of a slave in de compound makee too much noise. De man what stand guard ketchee him and takee him to my grandpa. He sit up and lookee at de boy so. Den he astee him, ‘Whoever tellee you dat de mouse kin walk ’cross de roof of de mighty? Where is dat Portugee man? I swap you for tobacco! In de olden days, I walk on yo’ skin!’ (That is, I would kill you and make shoes from your hide.) ‘I drink water from yo’ skull.’ (I would have killed you and used your head for a drinking cup.)

Of King Glele of Dahomey, whose army sacked Bantè after it refused Glele’s demand for tribute, Kossola says, accurately:

De king of Dahomey, you know, he got very rich ketchin slaves. He keep his army all de time making raids to grabee people to sell so de people of Dahomey doan have no time to raise gardens an’ make food for deyselves.

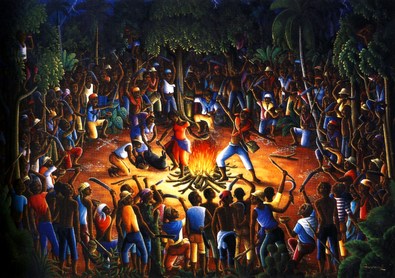

Dahomey appeared as a major power on the Bight of Benin (“the Slave Coast”) in the early 18th century. It was a state organized around slavery. Dahomey’s large,  well-trained standing army – including a famous corps of female warriors – launched annual campaigns to capture slaves for both the export market and domestic uses, including ritual sacrifice.

well-trained standing army – including a famous corps of female warriors – launched annual campaigns to capture slaves for both the export market and domestic uses, including ritual sacrifice.

Dahomey was a warrior state, with a deep-seated military ethos which involved a disdain for agriculture…the economic issue of the slave trade was bound up with the religious issue of human sacrifice. Human sacrifice in Dahomey was practised mainly at the ‘Annual Customs’, the principal public ceremony of the monarchy, at which victims were offered to the deceased kings of the Dahomian dynasty. Those killed on these occasions were principally captives taken in Dahomey’s wars, whose sacrifice served to celebrate Dahomian military prowess. Human sacrifice and the export slave trade were thus closely inter-connected, both being linked to Dahomian militarism, the former constituting part of its ideological superstructure and the latter an important aspect of its material foundation.

(Robin Law. The Politics of Commercial Transition: Factional Conflict in Dahomey in the Context of the Ending of the Atlantic Slave Trade. Journal of African History, 38 (1997) pp. 213-233.)

Kossola describes the Dahomian attack:

It bout daybreak when de folks dat sleep git wake wid de noise when de people of Dahomey breakee de Great Gate… I see de great many soldiers wid French gun in de hand and de big knife. Dey got de women soldiers too… Dey ketch people and dey saw de neck lak dis wid de knife den dey twist de head so and it come off de neck. Oh Lor’, Lor’!... I try to ’scape from de soldiers. I try to make it to de bush, but all soldiers over-take me befo’ I git dere. O Lor’, Lor’! When I think ’bout dat time I try not to cry no mo’… I no see none my family. I doan know where dey is. I beg de men to let me go findee my folks. De soldiers say dey got no ears for cryin’. De king of Dahomey come to hunt slave to sell. So dey tie me in de line wid de rest.

Their Dahomian captors marched Kossola and other townspeople from Bantè to Ouidah, the chief port on the Slave Coast. Here they were held in barracoons or slave-pens, for sale to foreign slave traders:

When we dere three weeks a white man come in de barracoon wid two men of de Dahomey. One man, he a chief of Dahomey and de udder one his word-changer. Dey make everybody stand in a ring—’bout ten folkses in each ring. De men by dey self, de women by dey self. Den de white man lookee and lookee. He lookee hard at de skin and de feet and de legs and in de mouth. Den he choose. Every time he choose a man he choose a woman. Every time he take a woman he take a man, too. Derefore, you unnerstand me, he take one hunnard and thirty. Sixty-five men wid a woman for each man. Dass right… Den we cry, we sad ’cause we doan want to leave the rest of our people in de barracoon. We all lonesome for our home. We doan know whut goin’ become of us, we doan want to be put apart from one ’nother.

Some history of African slavery

The Ghanaian scholar Dr. Akosua Perbi emphasizes that “From North to South, and from East to West, the African continent became intimately connected with slavery both as one of the principal areas in the world where slavery was common, and also as a major source of slaves for ancient civilization, the medieval world and all the continents of the modern period…”

That slavery was a widespread indigenous African institution, that Africa was from ancient times a major exporter of slaves to the rest of the world, and that these internal and external aspects reinforced and stimulated each other over time – this seems to be the most important “meta” hypothesis in my (admittedly cursory) reading on African slavery. Dr. Perbi continues:

The external dimension involved trade across the Sahara, the Mediterranean, the Red Sea, the Arabic and Indian ocean worlds. This trade began in ancient times and continued into the modern period. …The last phase of the external trade was that which involved the Oriental, Islamic and Atlantic worlds during the 15th to the 19th centuries…The internal trade was conducted within the African continent itself. It involved trade between North Africa and West Africa on the one hand and East, Central and Southern Africa on the other hand….When the first Europeans i.e. the Portuguese set foot on the shores of Ghana in 1471, they found in existence a brisk trade in slaves and other goods between Ghana and its coastal neighbors.” (Akosua Perbi. 2001. Slavery and the Slave Trade in Pre-Colonial Africa. Paper delivered at the University of Illinois.)

John Thornton, a historian of Africa and the Atlantic World at Boston University writes of internal African slavery that:

Slavery was widespread in Atlantic Africa because slaves were the only form of private revenue-producing property recognized in African law…Because of this legal feature, slavery was in many ways the functional equivalent of the landlord-tenant relationship and was perhaps as widespread…African law established claims on product through taxation and slavery rather than through the fiction of landownership.

The African social system was thus not backward or egalitarian, but only legally divergent. Although the origins and ultimate significance of this divergence are a matter for further research, one important result was that it allowed African political and economic elites to sell large numbers of slaves to whoever would pay and thus fueled the Atlantic slave trade. This legal feature made slavery and slave trading widespread, and its role in producing secure wealth linked it to economic development. (John K.Thornton. 1992. Africa and the Africans in the Making of the Atlantic World, 1400-1680. Cambridge University Press.)

On the external trade, the survey of African slavery by Paul Lovejoy estimates some 24 million slaves were exported from sub-Saharan Africa in the 11 centuries from 800 to 1900. (Paul E. Lovejoy. 2012. Transformations in Slavery: A History of Slavery in Africa. Third Edition. Cambridge University Press. African Studies, Book 117.) The Atlantic slave trade accounted for close to 13 million or a little over half of this total, while the Islamic slave trade to Muslim states in the Middle East, North Africa, Europe and Asia took the rest, over 11 million. (See table.)

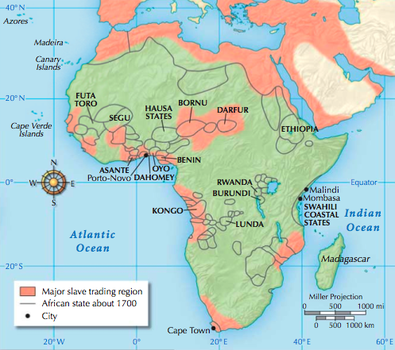

The Islamic slave trade dominated African slave exports in the period before 1600, taking 7.1 million slaves, according to Lovejoy’s estimates, with the main trade routes running overland across the Sahara, and by sea, across the Red Sea and from the coast of East Africa. Exploding demand for slave labor on the plantations of the New  World predominated after 1600, taking around 3 out of every four slaves exported. The main areas supplying the Atlantic trade were, in order of importance: West-Central Africa (the present-day Congo republics and Angola); the Bight of Benin or the Slave Coast; the Gold Coast (Ghana); and the Bight of Biafra (the eastern coastline of Nigeria). The Islamic trade also grew in the period after 1600, on a century average basis, reaching a peak of 2.1 million in the 19th century.

World predominated after 1600, taking around 3 out of every four slaves exported. The main areas supplying the Atlantic trade were, in order of importance: West-Central Africa (the present-day Congo republics and Angola); the Bight of Benin or the Slave Coast; the Gold Coast (Ghana); and the Bight of Biafra (the eastern coastline of Nigeria). The Islamic trade also grew in the period after 1600, on a century average basis, reaching a peak of 2.1 million in the 19th century.

Most new slaves were secured by violence: war above all, but also slave raiding, banditry, and kidnapping. Other sources included tribute (backed by the threat of violence), judicial punishment, pawning of persons as security for debts, and, in rare cases, voluntary enslavement, to escape starvation for example.

And, whether in the domestic or external markets, in the Atlantic or Islamic trades, African actors dominated nearly all of the booming business in slaves, African states in particular. (See map.)

Thornton says of the Atlantic trade that, apart from the Portuguese colony of Angola:

Elsewhere along the African coast, the delivery of enslaved people to European shippers was an African business, managed by African commercial and political elites. European commercial records reveal this clearly. The records of the Dutch West India Company … provide clear support. If one takes the company’s business on the Gold Coast in the eighteenth century, the period of fullest records and greatest export of people – a record which probably exceeds 100,000 pages in length – there is scarcely any mention of direct enslavement of Africans. The records of French, English, and Danish companies, less complete and voluminous, but responsible for carrying many more slaves than the Dutch, tell us very much the same story. European merchants or companies acquired their slaves by purchase from African buyers, usually with the active participation of African states, both as taxing agencies and in their own right as commercial sellers.

Even in Angola, where, exceptionally, the Portuguese themselves became slave-hunters, they also continued to buy large numbers of slaves from African kingdoms and warlords further inland, in southern Congo, eastern Angola, and Northern Zambia.

Nor was it that outsiders coerced African rulers into carrying on the slave trade. Thornton continues:

It is equally obvious that African states had the upper hand if the game of force was to be played. Although Europeans often fortified their “factories,” as trading posts were usually called, these fortifications could not resist an attack by determined African authorities… Francisco Pereira Mendes, the Portuguese factor [at Ouidah] took great lengths to explain to his home government why it was impossible for him to resist the demands of the King of Dahomey when the latter’s armies appeared on the coast in 1727.

It is equally obvious that African states had the upper hand if the game of force was to be played. Although Europeans often fortified their “factories,” as trading posts were usually called, these fortifications could not resist an attack by determined African authorities… Francisco Pereira Mendes, the Portuguese factor [at Ouidah] took great lengths to explain to his home government why it was impossible for him to resist the demands of the King of Dahomey when the latter’s armies appeared on the coast in 1727.

Yet, although Africans controlled the trade, and could have stopped it within their own lands at virtually any time, they let it continue for centuries. Some areas were never a part of the slave trade, although they lay on the coast and occasionally traded with Europeans in other commodities. The stretch of coast from southern Liberia to eastern Ivory Coast, for example, never exported more than a handful of slaves. Similarly, the coast from southern Cameroon to Gabon was a marginal producer of slaves at best. Some entered and subsequently left the trade: the Kingdom of Benin is a fine example of this. Benin participated in the slave trade in the early sixteenth century, but then around 1550 abruptly broke it off, while continuing to deal with European merchants in other commodities like pepper and ivory. Then, from about 1715 until 1735, it participated again, astonishing the Dutch merchants who were not prepared to purchase slaves at that source. But after 1735, Benin again stopped selling slaves while continuing its commerce in other commodities.

(John K. Thornton. 2012. A Cultural History of the Atlantic World. 1250-1820. Cambridge University Press.)

Colonization and the (incomplete) abolition of African slavery

Paul Lovejoy comes to the astonishing conclusion that “By the last decades of the nineteenth century, the African social order was more firmly rooted in slavery than ever before.” (Lovejoy, 2012, Chapter 11 “The Abolitionist Impulse.”) It was only external  pressure that began to curb African slavery in the latter part of the 19th and into the 20th century.

pressure that began to curb African slavery in the latter part of the 19th and into the 20th century.

The Atlantic slave trade went down first, following the abolition of the external slave trade by Britain and others in the early 19th century, and the abolition of internal slavery within the Caribbean colonies, the United States and various Latin American countries over the course of the century.

The abolition of African internal slavery and the Islamic slave trade took longer and is not entirely complete even now. Christian missionaries were at the forefront of this movement, supported, eventually, by political action, in the wake of the European colonization of Africa at the end of the 19th century. Britain proclaimed the abolition of slavery on the Gold Coast in 1874, following the third Anglo-Asante War, for example. Although Britain did not fully colonize the Asante kingdom until 1902, thousands of slaves escaped their Asante masters and fled to the British protectorate after the proclamation of 1874, many becoming highly motivated soldiers in the British colonial army. Entire villages of slaves sought sanctuary with the Christian missions.

But European powers hesitated to pursue abolition of domestic slavery or to allow Christian missionaries in their new, more heavily Islamic colonies in the Sahelian belt stretching from Senegal on the Atlantic to Sudan on the Red Sea. Lovejoy describes how the French sought to placate local Muslim elites by returning escaped slaves to their masters, reclassifying slaves as “servants” or “adopted family members” and otherwise undermining a long-standing French commitment to the abolition of slavery. The policy of accommodating domestic Islamic slavery was also adopted by the British after their occupation of Sudan in 1896. British colonial officials became experts on Islamic law, interpreting its provisions on slavery in a manner that would justify its continuation, with modifications.

Nonetheless, says Lovejoy, these efforts by colonial regimes to accommodate domestic slavery in the Sahelian zone failed to prevent a “massive flight of slaves in the 1890s and the first decade of the twentieth century. Throughout the savanna, slaves ran away, particularly slaves who had been on plantations. The most dramatic struggle occurred in French area… [in] centers of plantation agriculture… The scale of desertion was so great that it shook the foundations of the Muslim states as much or more than the colonial conquest itself.”

The scale of the exodus was so large that it represents one of the most significant slave revolts in history. There were many efforts to stop the flight before 1905, but once the exodus began, nothing could be done. The French simply let the slaves go, and for the first time the French restrained the masters. Once the dust had settled, the remnants of the slave system were reassembled, only now the more patriarchal dimensions of slavery were predominant. The French, like the British in the Nile valley and the Sokoto Caliphate, upheld Islamic law and custom in supporting slavery, with the expectation that slavery would gradually disappear now that the most disgruntled elements of the slave population had left. (Lovejoy, 2012. Chapter 11.)

Even now, says the Anti-Slavery Society, descent-based slavery “can still be found across the Sahel belt of Africa, including Mauretania, Niger, Mali, Chad, and Sudan.” Francis Bok, an African of Southern Sudanese Dinka ancestry, tells of his capture and enslavement by Arab ‘janjaweed” militia in 1986, when he was seven years old.